Every weekend, I shed every article of clothing on a stage at the historic Theatre Row as I vocalize and smile shamelessly in Naked Boys Singing. This show marks my eighth stage production in New York: and while I have previously worked at The Metropolitan Opera, Carnegie Hall, The Barrow Group and a half-dozen other Off or Off-Off Broadway theaters, taking this job represented stepping outside of my comfort zone in several regards. It is my first musical role and I had just three rehearsals before my first performance. But of course, the question I’ve been asked most since I started working in this show has been some form of: “Are you completely naked onstage? The entire time? What is that like?” I hear the curiosity in their voice, as if this is some particularly bold or brave move on my part. Another friend voiced concern that this would limit how others might see me professionally and the opportunities that I would be afforded moving forward in my career.

In taking this job, I considered only briefly if others would lose respect for me. Anyone who knows me well knows that I am a curious and passionate artist not afraid to take calculated risks and put myself out there. And for me personally, if a role requires nudity, that is just the character’s costume. Perhaps my thinking is not so far removed from that of the ancient Greeks, who celebrated the human body and nudity in their culture and art served as a costume that indicated a specific character role or trait of its subject. History lesson aside, I have always felt that an actor should be able to use all of his/her body as the instrument to serve the work, which means I don’t particularly feel embarrassed or awkward with revealing any or all of my body for a piece of material that appeals to me. I very much wanted to do this job for several reasons which I will articulate further. And when you’ve been onstage for an hour and are completely engaged in executing the singing, dancing and comedy, there simply isn’t the time or mental space for any kind of self-consciousness about being naked. As with any role, you’re in the moment and it just happens.

In fact, I find nudity to be rather empowering. It is one of the more vulnerable things you can do as an actor as there are quite literally no layers between you and the audience. It has made me an infinitely more confident performer: any fear that you might have about live performance is eradicated out of necessity. You are in complete control of the audience and it can be a transformative experience: whatever stage presence you inherently bring as an artist is amplified as their gaze is transfixed on you. Properly used, nudity is a powerful theatrical tool that can evoke pathos, sensuality, desire, shock or just about any emotion. And there are different types of bodies in this cast, which has made the juxtaposition of our nude forms even more poignant and self-affirming. We are all gay men and uniquely beautiful in our own imperfect way: we are not a homogeneous lot.

The situational irony is that with each show, I find myself more concerned with bringing details to my performance that have less to do with nudity at face value. What I love about the show is that it is an opportunity to play broad comedy inhabiting more than one persona – akin to my days studying at The Groundlings School where we devoted weeks to developing different characters. And in this production, I’m also interested in exploring where funny and sexy intersect. There is a longstanding cultural seriousness about nudity that stems in part from our Puritanical roots. Another consideration: some may perceive that something cannot be at once comedic and sexually appealing, as if those two synapses of their brain cannot fire simultaneously. I was hoping that doing this show would allow me to bridge that gap in my own work. For instance, in the number “Bliss of a Bris”, I wear a kippah as I play a character who celebrates his circumcision. For obvious reasons, I wouldn’t seem an immediate casting choice to play this track but I show up as myself and make it my own. And I am ever grateful to Michael and Tom D’Angora for giving me that opportunity to stretch.

I also don’t believe nudity stigmatizes a career any longer. Consider Daniel Radcliffe, who was praised a decade ago for his turn in Peter Shaffer’s Equus when he was only 17, Kathleen Turner who disrobed in the West End production of The Graduate, or Nicole Kidman, who made her debut at the Donmar Warehouse in 1998 in The Blue Room, David Hare’s sexually-charged adaptation of Arthur Schnitzler’s La Ronde. When Ian McKellen exposed himself in Trevor Nunn’s production of King Lear, feminist critic Germaine Greer wrote, “The most memorable moment, for many of us the only memorable moment… is when Ian McKellen drops his trousers and displays his impressive genitalia to the audience.”

I think nudity was a much more courageous thing for an actor to do when Sally Kirkland did it on the New York stage in the ‘60s. In Terrence McNally’s one-act play Sweet Eros, which premiered Off-Broadway in 1968 at the Gramercy Arts Theatre, she sat bound and naked in a chair for forty-five minutes, saying nothing. In July 1969, TIME anointed her “the latter-day Isadora Duncan of nudothespianism” and per People Magazine, “Kirkland was to nakedness what Walt Disney was to animation,” and her nudity made her the center of numerous debates on morality in the arts. Two decades later, she went on to receive an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress and she famously beat Meryl Streep, Glenn Close and Holly Hunter at the Golden Globes. So despite any controversy that sparked from Kirkland’s choice to take on nude roles in her early career, her talent ultimately prevailed.

Whether to play a role that involves nudity is a choice that remains with the individual artist. It is a personal, creative and professional choice and no one else can make that choice for you, be they a manager, agent, parent, intimate partner or friend. So don’t let fear or the opinions of others dictate that decision, which is yours to make alone, and in terms of theater history you’re in good company if you decide to bare all.

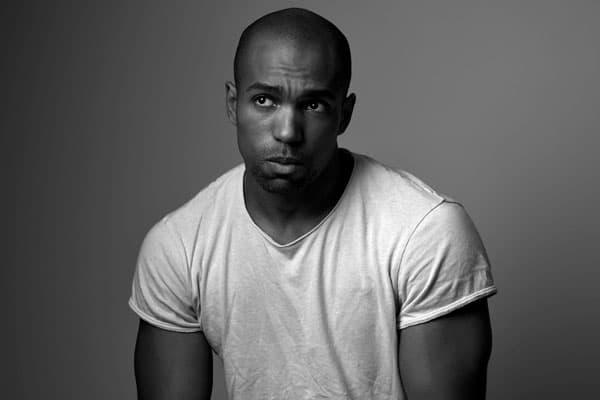

Adam Davenport graduated from Yale University and is a Billboard-charting artist; last summer, his debut single “My Return Address is You,” featuring Shanica Knowles, charted on the Dance Club chart for 10 weeks, where it surpassed tracks from the likes of Selena Gomez, Demi Lovato and Zedd. He recently co-starred in High Maintenance on HBO and appeared in Sir David McVicar’s production of Tosca at The Met. This spring, he won an Independent Music Award at Lincoln Center. He also co-produced the feature film Furlough, released by IFC Films, starring Tessa Thompson, Melissa Leo, Edgar Ramirez, Whoopi Goldberg and Anna Paquin. He is one of the few African-Americans to be featured by DNA Magazine Australia, which named him on their Best of 2016 list. This year he was accepted into the Recording Academy as a voting member of the Grammy Awards and he has served on the nominating committee for the NAACP Image Awards for the past decade. He is a member of the Screen Actors Guild and Actors Equity Association. You can find Adam on IMDB, Instagram and Facebook.